Epstein Maxwell The Full Shocking Story

https://www.inltv.co.uk/index.php/epsteinmaxwell-thefullshockingstory

Ghislaine Maxwell May Spend Up To 65 years in Prison Having Being Convicted of recruiting underage girls to be sexually abused by Epstein

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part One

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part Two

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part Three

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part Four

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part Five

Jeffrey Epstein And Ghislaine Maxwell Clan Exposed The Whole Shocking Truth

The Complete Epstein Maxwell Story Part Six

John Preston Talks About Robert Maxwell's Mysterious Death

The Bizarre Life And Death Of Robert Maxwell 2.5 Hours

Das Milliardengeschäft Des Robert Maxwell -Dokumentary1994

The Mystery Of The Fall Of Robert Maxwell-by John Preston

Robert Maxwell Interview Evening News Re-Launch

TN-86-108-013-THAMES NEWS. 18.8.86

Robert Maxwell Oxford United 1984 TV Feature,

Marking Three Years Since Robert Maxwell Took Over The Club

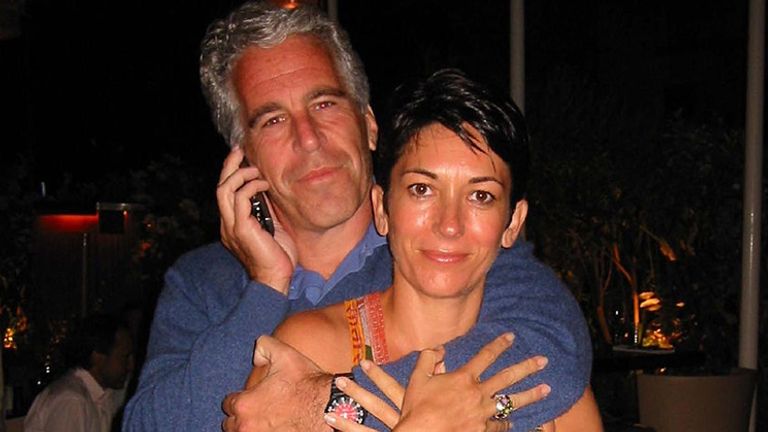

Photos appeared to show Maxwell and Epstein had a close relationship

Ghislaine Maxwell May Spend Up To 65 years in Prison Having Being Convicted of recruiting underage girls to be sexually abused by Epstein

Ghislaine Maxwell was 'main enforcer' and 'you don't cross her', says woman allegedly raped by Jeffrey Epstein

Maxwell has been convicted of recruiting underage girls to be sexually abused by Epstein and now faces up to 65 years in prison in the US.

A woman who claims Ghislaine Maxwell forced her into a room to be raped by Jeffrey Epstein has told Sky News that the British socialite was the "main enforcer".

Sarah Ransome said "you don't cross her" and she was "the lady of the house".

Maxwell has been convicted of recruiting underage girls to be sexually abused by former boyfriend Epstein and now faces up to 65 years in prison in the US.

She was found guilty of five of the six counts brought about by the testimony of four women who all gave evidence in court in New York.

Ms Ransome, who settled a lawsuit with Epstein and Maxwell in 2018, was not among the four but she did attend the trial.

She said it was important for her to be in court to "smile right back" at the defendant as she said Maxwell had smiled at her after allegedly forcing her into one of Epstein's rooms to be abused by the financier.

She told Sky's US correspondent Martha Kelner: "Ghislaine was the main enforcer… even before I met Ghislaine, Jeffrey said 'you answer to Ghislaine'. She is the lady of the house… you just don't cross her.

"She forced me into Jeffrey's room to be raped. And then when I walked out - well, walked, limped, I mean whatever you do when you have just been brutally raped... I looked at her.

"That's why it was really important for me to be there (at the court) and look at her because when I looked at her after she forced me into that room to be raped she smiled, and that's why I had to be there because you know what? I smiled right back at her when I saw her."

Meanwhile, one of the four accusers who testified in court against Maxwell said her conviction was "one important step" toward justice.

"It's a tremendous relief," Annie Farmer said on ABC's Good Morning America. "I wasn't sure that this day would ever come."

Ms Farmer, the only one of the four to give her full name in the trial, added: "I just feel so grateful that the jury believed us and sent a strong message that perpetrators of sexual abuse and exploitation will be held accountable no matter how much power and privilege they have."

Ms Farmer was 16-years-old when she first met Epstein. She claimed she was flown to his ranch in New Mexico under the impression it was part of a scholarship programme with dozens of other students, but arrived to find she was there alone, apart from Epstein and Maxwell.

She said Maxwell instructed her how to give a foot massage to Epstein and later massaged Ms Farmer's "chest and upper breasts".

Ms Farmer is now a psychologist, treating patients who have had similar experiences.

She said: "Having the privilege of hearing so many stories from the people that I work with, I have really recognised that it's a very rare opportunity to be able to be in court and tell your story.

"And to be able to see the person who perpetrated the abuse held accountable.

Annie Farmer testified in court against Maxwell.

Ghislaine Maxwell and her former boyfriend Jeffrey Epstein

Ghislaine Maxwell, youngest child of media proprietor and fraudster, Ian Robert Maxwell (1923 - 1991), holding a framed photograph of her late father Ian Robert Maxwell

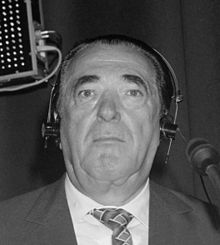

Ian Robert Maxwell

Ian Robert Maxwell MC (born Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch; 10 June 1923 – 5 November 1991) was a British media proprietor, former member of Parliament (MP), suspected spy, and fraudster.[1] Originally from Czechoslovakia, Maxwell rose from poverty to build an extensive publishing empire. After his death, huge discrepancies in his companies' finances were revealed, including his fraudulent misappropriation of the Mirror Group pension fund.[2]

Early in his life, Maxwell, then an Orthodox Jew, escaped from Nazi occupation, joined the Czechoslovak Army in exile during World War II and was decorated after active service in the British Army. In subsequent years he worked in publishing, building up Pergamon Press to a major publishing house. After six years as a Labour MP during the 1960s, Maxwell again put all his energy into business, successively buying the British Printing Corporation, Mirror Group Newspapers and Macmillan Publishers, among other publishing companies.

Maxwell had a flamboyant lifestyle, living in Headington Hill Hall in Oxford, from which he often flew in his helicopter, or his luxury yacht, the Lady Ghislaine. He was litigious and often embroiled in controversy. In 1989, Maxwell had to sell successful businesses, including Pergamon Press, to cover some of his debts. In 1991, his body was discovered floating in the Atlantic Ocean, having apparently fallen overboard from his yacht. He was buried in Jerusalem.

Maxwell's death triggered the collapse of his publishing empire as banks called in loans. His sons briefly attempted to keep the business together, but failed as the news emerged that the elder Maxwell had stolen hundreds of millions of pounds from his own companies' pension funds. The Maxwell companies applied for bankruptcy protection in 1992.

Early life of Robert Maxwell

Robert Maxwell was born into a poor Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jewish family in the small town of Slatinské Doly, in the region of Carpathian Ruthenia, Czechoslovakia (now Solotvyno, Ukraine).[3][4][5] His parents were Mechel Hoch and Hannah Slomowitz. He had six siblings. In 1939, the area was reclaimed by Hungary. Most members of Maxwell's family were murdered in Auschwitz after Hungary was occupied in 1944 by Nazi Germany, but he had years earlier escaped to France.[3] In May 1940, he joined the Czechoslovak Army in exile in Marseille.[6]

After the fall of France and the British retreat to Britain, Maxwell (using the name "Ivan du Maurier",[7] or "Leslie du Maurier",[8] the surname taken from the name of a popular cigarette brand) took part in a protest against the leadership of the Czechoslovak Army, and with 500 other soldiers he was transferred to the Pioneer Corps and later to the North Staffordshire Regiment in 1943. He was then involved in action across Europe, from the Normandy beaches to Berlin, and achieved the rank of sergeant.[3] Maxwell gained a commission in 1945 and was promoted to the rank of captain.

In January 1945, Maxwell's heroism in "storming a German machine-gun nest" during the war won him the Military Cross, presented by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.[9] Attached to the Foreign Office, he served in Berlin during the next two years in the press section.[5] Maxwell naturalised as a British subject on 19 June 1946[10] and changed his name by deed of change of name on 30 June 1948.[11]

In 1945, Maxwell married Elisabeth "Betty" Meynard, a French Protestant, and the couple had nine children over the next 16 years: Michael, Philip, Ann, Christine, Isabel, Karine, Ian, Kevin and Ghislaine.[12] In a 1995 interview, Elisabeth talked of how they were recreating his childhood family who were killed in the Holocaust.[13] Five of his children – Christine, Isabel, Ian, Kevin and Ghislaine – were later employed within his companies. His daughter Karine died of leukaemia at age three, while Michael was severely injured in a car crash in 1961, at the age of 15, when his driver fell asleep at the wheel. Michael never regained consciousness and died seven years later.[14][15][16]

After the war, Maxwell used contacts in the Allied occupation authorities to go into business, becoming the British and US distributor for Springer Verlag, a publisher of scientific books. In 1951, he bought three-quarters of Butterworth-Springer, a minor publisher; the remaining quarter was held by the experienced scientific editor Paul Rosbaud.[17] They changed the name of the company to Pergamon Press and rapidly built it into a major publishing house.[18]

In 1964, representing the Labour Party, Maxwell was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Buckingham and re-elected in 1966. He gave an interview to The Times in 1968, in which he said the House of Commons provided him with a problem. "I can't get on with men", he commented. "I tried having male assistants at first. But it didn't work. They tend to be too independent. Men like to have individuality. Women can become an extension of the boss."[19] Maxwell lost his seat in 1970 to Conservative challenger William Benyon. He contested Buckingham again in both 1974 general elections, but without success.

At the beginning of 1969, it emerged that Maxwell's attempt to buy the tabloid newspaper News of the World had failed.[20] The Carr family, which owned the title, was incensed at the thought of a Czechoslovak immigrant with socialist politics gaining ownership, and the board voted against Maxwell's bid without any dissent. The News of the World's editor, Stafford Somerfield, opposed Maxwell's bid in an October 1968 front page opinion piece, in which he referred to Maxwell's Czechoslovak origins and used his birth name.[21] He wrote, "This is a British paper, run by British people ... as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding ... Let us keep it that way".[22] The paper was later purchased by Australian tycoon Rupert Murdoch, who later that year acquired The Sun, which had also previously interested Maxwell.[23]

Pergamon lost and regained

In 1969, Saul Steinberg, head of "Leasco Data Processing Corporation", was interested in a strategic acquisition of Pergamon Press. Steinberg claimed that during negotiations, Maxwell falsely stated that a subsidiary responsible for publishing encyclopedias was extremely profitable.[24][25] At the same time, Pergamon had been forced to reduce its profit forecasts for 1969 from £2.5 million to £2.05 million during the period of negotiations, and dealing in Pergamon shares was suspended on the London stock markets.[25]

Maxwell subsequently lost control of Pergamon and was expelled from the board in October 1969, along with three other directors in sympathy with him, by the majority owners of the company's shares.[26] Steinberg purchased Pergamon. An inquiry by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) under the Takeover Code of the time reported was conducted by Rondle Owen Charles Stable and Sir Ronald Leach in mid-1971.[27][5] The report concluded: "We regret having to conclude that, notwithstanding Mr Maxwell's acknowledged abilities and energy, he is not in our opinion a person who can be relied on to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company."[28][29] It was found that Maxwell had contrived to maximise Pergamon's share price through transactions between his private family companies.[24]

At the same time, the United States Congress was investigating Leasco's takeover practices. Judge Thayne Forbes in September 1971 was critical of the inquiry: "They had moved from an inquisitorial role to accusatory one and virtually committed the business murder of Mr. Maxwell." He further continued that the trial judge would probably find that the inspectors had acted "contrary to the rules of natural justice".[30] The company performed poorly under Steinberg; Maxwell reacquired Pergamon in 1974 after borrowing funds.[31]

Maxwell established the Maxwell Foundation in Liechtenstein in 1970. He acquired the British Printing Corporation (BPC) in 1981 and changed its name first to the British Printing and Communication Corporation (BPCC) and then to the Maxwell Communications Corporation (MCC). The company was later sold in a management buyout and is now known as Polestar.

Later business activities of Robert Maxwell

In July 1984, Maxwell acquired Mirror Group Newspapers, the publisher of six British newspapers, including the Daily Mirror, from Reed International plc.[32] for £113 million.[33] This led to the famous media war between Maxwell and Murdoch, the proprietor of the News of the World and The Sun.

Mirror Group Newspapers (formerly Trinity Mirror, now part of Reach plc), published the Daily Mirror, a pro-Labour tabloid; Sunday Mirror; Sunday People; Scottish Sunday Mail and Scottish Daily Record. At a press conference to publicise his acquisition, Maxwell said his editors would be "free to produce the news without interference".[32] Meanwhile, at a meeting of Maxwell's new employees, Mirror journalist Joe Haines asserted that he was able to prove that their boss "is a crook and a liar".[34][35] Haines quickly came under Maxwell's influence and later wrote his authorised biography.[34]

In June 1985 Maxwell announced a takeover of Clive Sinclair's ailing home computer company, Sinclair Research, through Hollis Brothers, a Pergamon subsidiary.[36] The deal was aborted in August 1985.[37] In 1987 Maxwell purchased part of IPC Media to create Fleetway Publications. The same year he launched the London Daily News in February after a delay caused by production problems, but the paper closed in July after sustaining significant losses contemporary estimates put at £25 million.[38] At first intended to be a rival to the Evening Standard, Maxwell had made a rash decision for it to be the first 24-hour paper as well.[39]

By 1988 Maxwell's various companies owned, in addition to the Mirror titles and Pergamon Press, Nimbus Records, Maxwell Directories, Prentice Hall Information Services and the Berlitz language schools. He also owned a half-share of MTV in Europe and other European television interests, Maxwell Cable TV and Maxwell Entertainment.[31] Maxwell purchased Macmillan Publishers, the American firm, for $2.6 billion in 1988. In the same year, he launched an ambitious new project, a transnational newspaper called The European. In 1991 Maxwell was forced to sell Pergamon and Maxwell Directories to Elsevier for £440 million to cover his debts;[31] he used some of this money to buy an ailing tabloid, the New York Daily News. The same year Maxwell sold 49 percent of the stock of Mirror Group Newspapers to the public.[5]

Maxwell's links with Eastern European totalitarian regimes resulted in several biographies[40] of those countries' leaders, with interviews conducted by Maxwell, for which he received much derision.[5] At the beginning of an interview with Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu, then the country's communist leader, he asked, "How do you account for your enormous popularity with the Romanian people?"[41]

Maxwell was also the chairman of Oxford United, saving them from bankruptcy and attempting to merge them with Reading in 1983 to form a club he wished to call "Thames Valley Royals". He took Oxford into the top flight of English football in 1985 and the team won the League Cup a year later. Maxwell bought into Derby County in 1987. He also attempted to buy Manchester United in 1984, but refused owner Martin Edwards's asking price.

A bugged version of the intelligence spy software PROMIS was sold in the mid-1980s for Soviet government use, with Robert Maxwell as a conduit.[43]

Maxwell was known to be litigious against those who would speak or write against him. The satirical magazine Private Eye lampooned him as "Cap'n Bob" and the "bouncing Czech",[44] the latter nickname having originally been devised by Prime Minister Harold Wilson[45] (under whom Maxwell was an MP). Maxwell took out several libel actions against Private Eye, one resulting in the magazine losing an estimated £225,000 and Maxwell using his commercial power to hit back with a one-off spoof magazine Not Private Eye.[46]

Israeli controversy

1948 war

A hint of Maxwell's service to Israel was provided by John Loftus and Mark Aarons, who described Maxwell's contacts with Czechoslovak communist leaders in 1948 as crucial to the Czechoslovak decision to arm Israel in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Czechoslovak military assistance was both unique and crucial for Israel as it battled for its existence. According to Loftus and Aarons, it was Maxwell's covert help in smuggling aircraft parts into Israel that led to the country having air superiority during their 1948 war of independence.[47]

Mossad allegations; Vanunu case

The Foreign Office suspected that Maxwell was a secret agent of a foreign government, possibly a double agent or a triple agent, and "a thoroughly bad character and almost certainly financed by Russia". He had known links to the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), to the Soviet KGB, and to the Israeli intelligence service Mossad.[48] Six serving and former heads of Israeli intelligence services attended Maxwell's funeral in Israel, while Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir eulogised him and stated: "He has done more for Israel than can today be told."[49]

Shortly before Maxwell's death, a former employee of Israel's Military Intelligence Directorate, Ari Ben-Menashe, approached a number of news organisations in Britain and the US with the allegation that Maxwell and the Daily Mirror's foreign editor, Nicholas Davies, were both long-time agents for Mossad. Ben-Menashe also claimed that, in 1986, Maxwell informed the Israeli Embassy in London that Mordechai Vanunu revealed information about Israel's nuclear capability to The Sunday Times, then to the Daily Mirror. Vanunu was subsequently kidnapped by Mossad and smuggled to Israel, convicted of treason and imprisoned for eighteen years.[50]

Ben-Menashe's story was ignored at first, but eventually journalist Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker repeated some of the allegations during a press conference in London held to publicise The Samson Option, Hersh's book about Israel's nuclear weapons.[51] On 21 October 1991, Labour MP George Galloway and Conservative MP Rupert Allason (also known as espionage author Nigel West) agreed to raise the issue in the House of Commons under parliamentary privilege protection,[a] which in turn allowed British newspapers to report events without fear of libel suits. Maxwell called the claims "ludicrous, a total invention" and sacked Davies.[52] A year later, in Galloway's libel settlement against Mirror Group Newspapers (in which he received "substantial" damages), Galloway's counsel announced that the MP accepted that the group's staff had not been involved in Vanunu's abduction. Galloway referred to Maxwell as "one of the worst criminals of the century".[53]

Death of Robert Maxwell

On 4 November 1991, Maxwell had an argumentative phone call with his son Kevin over a meeting scheduled with the Bank of England on Maxwell's default on £50,000,000 in loans. Maxwell missed the meeting, instead travelling to his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, in the Canary Islands, Spain.[9]

On 5 November, Maxwell was last in contact with the crew of Lady Ghislaine at 4:25 a.m. local time, but was found to be missing later in the morning.[52] It has been speculated that Maxwell was urinating into the ocean nude at the time, as he often did.[9] He was presumed to have fallen overboard from the vessel, which was cruising off the Canary Islands, southwest of Spain.[52][54] Maxwell's naked body was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean and taken to Las Palmas.[50] Besides a "graze to his left shoulder", there were no noticeable wounds on Maxwell's body.[9] The official ruling at an inquest held in December 1991 was death by a heart attack combined with accidental drowning,[55] although three pathologists had been unable to agree on the cause of his death at the inquest;[50] he had been found to have been suffering from serious heart and lung conditions.[56] Murder was ruled out by the judge and, in effect, so was suicide.[55] His son discounted the possibility of suicide, saying, "I think it is highly unlikely that he would have taken his own life, it wasn't in his makeup or his mentality."[9]

Maxwell was afforded a lavish funeral in Israel, attended by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, Israeli President Chaim Herzog, at least six serving and former heads of Israeli intelligence[57] and many dignitaries and politicians, both government and opposition, and was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.[58][59][60] Herzog delivered the eulogy and the Kaddish was recited by his fellow Holocaust survivor, friend and longtime attorney Samuel Pisar.[61]

British Prime Minister John Major said Maxwell had given him "valuable insights" into the situation in the Soviet Union during the attempted coup of 1991. He was a "great character", Major added. Neil Kinnock, then Labour Party leader, spoke of him as a man with "a zest for life" who "attracted controversy, envy and loyalty in great measure throughout his rumbustious life."

A production crew conducting research for Maxwell, a 2007 biographical film by the BBC, uncovered tapes stored in a suitcase owned by his former head of security, John Pole. Later in his life, Maxwell had become increasingly paranoid about his own employees and had the offices of those he suspected of disloyalty bugged so he could hear their conversations. After Maxwell's death, the tapes remained in Pole's suitcase and were discovered by the researchers only in 2007.[62]

Aftermath: discovery of pension funds theft and collapse of a publishing empire

Maxwell's death triggered instability for his publishing empire, with banks frantically calling in their massive loans. Despite the efforts of his sons Kevin and Ian, the Maxwell companies soon collapsed. It emerged that, without adequate prior authorisation, Maxwell had used hundreds of millions of pounds from his companies' pension funds to shore up the shares of the Mirror Group to save his companies from bankruptcy.[63] Eventually, the pension funds were replenished with money from investment banks Shearson Lehman and Goldman Sachs, as well as the British government.[64] This replenishment was limited and also supported by a surplus in the printers' fund, which was taken by the government in part payment of £100 million required to support the workers' state pensions. The rest of the £100 million was waived. Maxwell's theft of pension funds was therefore partly repaid from public funds. The result was that in general, pensioners received about half of their company pension entitlement.

The Maxwell companies filed for bankruptcy protection in 1992. Kevin Maxwell was declared bankrupt with debts of £400 million. In 1995, Kevin, Ian and two other former directors went on trial for conspiracy to defraud, but were unanimously acquitted by a twelve-person jury the following year.

Family of Robert Maxwell

In November 1994, Maxwell's widow Elisabeth published her memoirs, A Mind of My Own: My Life with Robert Maxwell,[65] which sheds light on her life with him, when the publishing magnate was ranked as one of the richest people in the world.[66] Having earned her degree from Oxford University in 1981, Elisabeth devoted much of her later life to continued research on the Holocaust and worked as a proponent of Jewish-Christian dialogue. She died on 7 August 2013.[67]

In July 2020, Maxwell's youngest child, his daughter Ghislaine Maxwell, was arrested and charged in New Hampshire, US, with six federal crimes, involving minors' trade, travel and seducing to engage in criminal sexual activity, and conspiracy to entice children to engage in illegal sex acts, allegedly linked to a sex-trafficking ring with Jeffrey Epstein (who had already died in jail the previous year). She was convicted on 29 December 2021. [68]

In popular culture of Robert Maxwell

- Maxwell, in addition to Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch, was used as inspiration for the villainous media baron Elliot Carver in the 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, as well as its novelisation and video game adaptation.[69][70] At the film's conclusion, M orders a story spun disguising Carver's demise, saying that Carver is believed to have committed suicide by jumping off his yacht in the South China Sea.

- A BBC drama, Maxwell, covering his life shortly before his death, starring David Suchet and Patricia Hodge, was aired on 4 May 2007.[71] Suchet won the International Emmy Award for Best Actor for his performance as Maxwell.[72]

- A one-person show about Maxwell's life, Lies Have Been Told, written by Rod Beacham, was performed by Phillip York at London's Trafalgar Studios in 2006.[73]

- The Fourth Estate, a 1996 novel by Jeffrey Archer, is based on the lives of Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch.[74]

- Max, a novel by Juval Aviv, is based on Aviv's investigation into the death of Robert Maxwell.[75]

- Maxwell pressured Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev to cancel the contract between Elorg and Nintendo concerning the rights to the game Tetris.[76]

- In the 1992 final series of British sitcom The New Statesman, a recurring joke is Alan B'Stard's knowledge that Maxwell faked his death and is still alive. In the fifth episode, B'Stard visits war-torn Herzegovina, ostensibly to negotiate a peace treaty, but his plan all along has been to smuggle Maxwell out of the country to a luxury hideaway, in return for a handsome slice of the Mirror Group funds. It transpires, however, that Maxwell has already spent the money, and the episode ends with a vengeful B'Stard giving him "an amazing deja-vu experience" by pushing him over the side of his yacht, where he presumably dies.

See also

- Daily News (Perth, Western Australia) §1980–1990

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

- Maxwellisation

- Scottish Daily News

Notes

- ^ Parliamentary privilege allows MPs to ask questions in Parliament without risk of being sued for defamation.

References

- ^ "Robert Maxwell's sons speak out about their fraudster father". Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "A Notorious Fraud – the Robert Maxwell Farrago". Australian Guardians. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Марк Штейнберг. Евреи в войнах тысячелетий. p. 227. ISBN 5-93273-154-0 (in Russian)

- ^ Иван Мащенко (7–13 September 2002). Медиа-олигарх из Солотвина. Зеркало недели (in Russian) (#34 (409)). Archived from the original on 22 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Whitney, Craig R. (6 November 1991). "Robert Maxwell, 68: From Refugee to the Ruthless Builder of a Publishing Empire". The New York Times. p. 5.

- ^ "Ludvík Hoch (Maxwell) in the database of Central Military Archive in Prague".

- ^ Walters, Rob (8 December 2009). "Naughty Boys: Ten Rogues of Oxford". google.se. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ LLC, Sussex Publishers (May 1988). Spy. Sussex Publishers, LLC.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Kirsch, Noah. "Long Before Ghislaine Maxwell Disappeared, Her Mogul Father Died Mysteriously". Forbes.

- ^ "No. 37658". The London Gazette. 19 July 1946. p. 3739.

- ^ "No. 38352". The London Gazette. 13 July 1948. p. 4046.

- ^ Haines, Joe (1988). Maxwell. London: Futura. pp. 434 et seq. ISBN 0-7088-4303-4.

- ^ Witchell, Alex (15 February 1995). "AT LUNCH WITH: Elisabeth Maxwell; Questions Without Answers". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Maxwell: The final verdict

- ^ A mind of my own by Elisabeth Maxwell

- ^ Rampton, James (28 April 2007). "Maxwell was a monster - but much more, too". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Haines (1988) 135

- ^ Cox, Brian (October 2002). "The Pergamon phenomenon 1951-1991: Robert Maxwell and scientific publishing". Learned Publishing. 15 (4): 273–278. doi:10.1087/095315102760319233.

- ^ Barwick, Sandra (25 October 1994). "The beast and his beauties". The Independent.

- ^ "1969: Murdoch wins Fleet Street foothold". BBC. 2 January 1969.

- ^ Greenslade, Roy (2004) [2003]. Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda. London: Pan. p. 395. ISBN 9780330393768.

- ^ Grundy, Bill (24 October 1968). "Mr Maxwell and the Ailing Giant". The Spectator. p. 6.

- ^ "The Maxwell Murdoch tabloid rivalry". BBC News. 5 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Dennis Barker and Christopher Sylvester "The grasshopper", – Obituary of Maxwell, The Guardian, 6 November 1991. Retrieved on 19 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nicholas Davenport "Money Wanted: A Board of Trade inquiry", The Spectator, 29 August 1969, p.24

- ^ Nicholas Davenport "Money: The End of the Affair", The Spectator, 17 October 1969, p.22

- ^ Stable, Rondle Owen Charles; Leach, Sir Ronald; Industry, Great Britain Department of Trade and (1971). Report on the Affairs of the International Learning Systems Corporation Limited: And Interim Report on the Affairs of Pergamon Press Limited, Investigation Under Section 165(b) of the Companies Act 1948. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-510728-3.

- ^ Stable, Rondle Owen Charles; Leach, Sir Ronald; Industry, Great Britain Department of Trade and (1971). Report on the Affairs of the International Learning Systems Corporation Limited: And Interim Report on the Affairs of Pergamon Press Limited, Investigation Under Section 165(b) of the Companies Act 1948. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-510728-3.

- ^ Wearing, Robert (2005). Cases in Corporate Governance. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 1412908779.

- ^ Betty Maxwell, p. 542

- ^ Jump up to:a b c "Robert Maxwell: Overview", keputa.net

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Briton Buys the Mirror Chain", The New York Times, 14 July 1984

- ^ Roy Greenslade Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda, London: Pan, 2004 [2003], p.395

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Say It Ain't So, Joe", The Spectator, 22 February 1992, p.15

- ^ Roy Greenslade Press Gang, p.395

- ^ "Sinclair to Sell British Unit". The New York Times. 18 June 1985. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Sinclair: A Corporate History". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Maxwell Closes London Paper", Glasgow Herald, 25 July 1987, p.3

- ^ Duncan Campbell "The London legacy of Cap'n Bob", The Guardian, 28 August 2006

- ^ David Ellis and Sidney Urquhart "Maxwell's Hall of Shame", Time, 8 April 1991

- ^ Editorial: "Breaking the Spell", The Spectator, 21 December 1991, p.3

- ^ "", Headington History

- ^ "In New French Best-Seller, Software Meets Espionage".

- ^ Jon Kelly "The strange allure of Robert Maxwell", BBC News, 4 May 2007

- ^ Reuters "Murdoch conclusion stirs memories of his old foe Maxwell", Chicago Tribune, 1 May 2012

- ^ "Not Private Eye", Tony Quinn, Magforum.com, 6 March 2007

- ^ John Loftus and Mark Aarons, The Secret War Against the Jews.

- ^ "FO Suspected Maxwell Was a Russian Agent, Papers Reveal". The Telegraph, 2 November 2003

- ^ Gordon Thomas (1999), Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad, New York: St. Martin's Press, p. 23

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Robert Verkaik "The Mystery of Maxwell's Death", The Independent, 10 March 2006

- ^ Hersh, Seymour M. (1991). The Samson Option : Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy (1st ed.). New York. pp. 312–15. ISBN 0-394-57006-5. OCLC 24609770.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ben Laurance and John Hooper, et al. "Maxwell's body found in sea", The Guardian, 6 November 1991

- ^ "Scottish MP wins libel damages", The Herald (Glasgow), 22 December 1992

- ^ "Robert Maxwell: A Profile". BBC News. 29 March 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Larry Eichel (14 December 1991). "Maxwell's Legacy Of Money Troubles Maxwell's Own Daily Mirror Newspaper Now Routinely Calls Him 'The Cheating Tycoon'". Philadelphia Inquirer

- ^ Marlise Simons (12 December 1991). "Autopsy Indicates Maxwell Did Not Drown". The New York Times.

- ^ Gordon Thomas. Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad, page 210

- ^ Clyde Haberman (11 November 1991). "The Media Business; Maxwell Is Buried In Jerusalem", The New York Times.

- ^ "Israel gives Maxwell farewell fit for hero". The Washington Post, 11 November 1991

- ^ "George Galloway sheds light on Maxwell family and its links to Jeffrey Epstein", 23 August 2019

- ^ "Maxwell, Colossus Even in Death, Laid to Rest on Mount of Olives", jta.org, 11 November 1991

- ^ "BBC reveals secret Maxwell tapes". BBC. 25 April 2007.

- ^ Prokesch, Steven (24 June 1992). "Maxwell's Mirror Group Has $727.5 Million Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Chapter 11: Major Corporate Governance Failures

- ^ Diski, Jenny (26 January 1995). "Bob and Betty". London Review of Books. 17 (2). Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ MacIntyre, Ben (1 January 1995). "A Match for Robert Maxwell". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Roy Greenslade, "Betty, Robert Maxwell's widow, dies aged 92", The Guardian (9 August 2013)

- ^ "Ghislaine Maxwell, confidante of Jeffrey Epstein, arrested on federal charges", The Wall Street journal, 2 July 2020.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (19 December 1997). "'TOMORROW NEVER DIES': JAMES BOND ZIPS INTO THE '90S". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Turner, Kyle (30 May 2018). "There's No News Like Fake News: Tomorrow Never Dies Today". Paste Magazine. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Suchet in title role of BBC Two's Maxwell". bbc.co.uk. 16 February 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Luft, Oliver (25 November 2008). "UK scoops seven International Emmys". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Benedict Nightingale. "Portrait of a megalomaniac." The Times, London, 13 January 2006: pg 39.

- ^ Archer, Jeffrey (1996). The Fourth Estate (First ed.). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0002253186.

- ^ Aviv, Juval (2006). Max (First ed.). London: Random House UK. ISBN 1844138755.

- ^ Ichbiah, Daniel (1997). La Saga des Jeux Vidéo (in French) (1st ed.). Pix'N Love Editions. p. 95. ISBN 2266087630.

Further reading[edit]

- Short BBC profile of Robert Maxwell

- Department of Trade and Industry report on Maxwell's purchase of the Mirror Group at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2004)

- Biography

- Hersh, Seymour (1991). The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Random House. ISBN 0-394-57006-5.

- Thomas, Gordon and Dillon, Martin. (2002). Robert Maxwell: Israel's Superspy: The Life and Murder of a Media Mogul, Carroll and Graf, ISBN 0-7867-1078-0

- Henderson, Albert, (2004) The Dash and Determination of Robert Maxwell, Champion of Dissemination, LOGOS. 15,2, pp. 65–75.

- Martin Dillon, The Assassination of Robert Maxwell, Israeli Superspy

- Joe Haines (1988) Maxwell, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-48929-6 .

- Robert N. Miranda (2001) Robert Maxwell: Forty-four years as Publisher, in E. H. Frederiksson ed., A Century of Science Publishing, IOS Press ISBN 1-58603-148-1

- Bower Tom Maxwell the final verdict Harper Collins 1996 ISBN 0-00-638424-2

- Bower Tom Maxwell the outsider Mandarin ISBN 0-7493-0238-0

- Roy Greenslade (1992) Maxwell: The Rise and Fall of Robert Maxwell and His Empire. ISBN 1-55972-123-5

- Roy Greenslade (2011) "Pension plunderer Robert Maxwell remembered 20 years after his death". The Guardian, 3 November 2011. Accessed 20 October 2013

- Coleridge, Nicholas (March 1994). Paper Tigers: The Latest, Greatest Newspaper Tycoons. Secaucus, NJ: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 9781559722155.

Ghislaine Maxwell

On 2 July 2020, Maxwell was arrested and charged by the federal government of the United States with the crimes of enticement of minors and sex trafficking of underage girls, related to her association with Epstein.[10] On 29 December 2021, she was convicted on five counts, including one of sex trafficking of a child.[2][3][4]Ghislaine Noelle Marion Maxwell (/ˌɡiːˈleɪn, -ˈlɛn/ ghee-LAYN, -LEN; born 25 December 1961)[5][6] is a British former socialite,[7] convicted of sex trafficking and other offences[8] connected with the financier and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. She worked for her father Robert Maxwell until his death in 1991, when she moved to the United States and became a close associate of Epstein. Maxwell founded a non-profit group for the protection of oceans, The TerraMar Project, in 2012. The organisation announced cessation of operations on 12 July 2019, a week after the sex trafficking charges brought by New York federal prosecutors against Epstein became public.[9] Maxwell is a naturalised US citizen but retains citizenship of the UK and France.[1]

Ghislaine Maxwell was born in 1961, in Maisons-Laffitte, Yvelines, France,[11] the ninth and youngest child of Elisabeth (née Meynard), a French-born scholar, and Robert Maxwell, a Czechoslovak-born British media proprietor. Her father was from a Jewish family, and her mother was of Huguenot (French Protestant) descent. Maxwell was born two days before a car accident that left her fifteen-year-old brother Michael in a prolonged coma until his death in 1967.[12] Her mother later reflected that the accident had an effect on the entire family, and surmised that Ghislaine had shown signs of anorexia while still a toddler.[12] Throughout childhood, Ghislaine lived with her family in Oxford at Headington Hill Hall, a 53-room mansion, where the offices of Pergamon Press, a publishing company run by Robert Maxwell, were also located.[9][11][13] Her mother said that all her children were brought up as Anglicans.[14] She studied at Oxford High School for Girls in North Oxford. Maxwell was enrolled at Edgarley Hall boarding school in Somerset aged nine, followed by Headington School at thirteen.[15] Maxwell attended Marlborough College[5] where she studied modern history with languages before going on to earn a degree from Balliol College, Oxford[5] in 1985.[15]

Maxwell had a close relationship with her father and was widely credited with being her father's favourite.[9][16][17] According to Tatler, Maxwell recalled that her father installed computers at Headington in 1973 and her first job was training to use a Wang and later programming code.[18] The Times reported that he did not permit Ghislaine to bring her boyfriends home or to be seen with them publicly, after she started attending Oxford University.[19][6]

Career of Ghislaine Maxwell

Ghislaine Maxwell was a prominent member of the London social scene in the 1980s.[20] She founded a women's club named after the original Kit-Cat Club[17][21] and was a director of Oxford United Football Club during her father's ownership.[22][23] She also worked at The European,[24] a publication Robert Maxwell had established. According to Tom Bower, writing for The Sunday Times, in 1986 Robert Maxwell invited her to the naming in her honour of his new yacht the Lady Ghislaine, at a shipyard in the Netherlands.[25] Maxwell spent a large amount of time in the late 1980s aboard the yacht, which was equipped with a Jacuzzi, sauna, gym and disco.[26] The Scotsman said Robert Maxwell had also "tailor-made a New York company for her".[27] The company, which dealt in corporate gifts, was not profitable.[19][25][28]

The Sunday Times reported that Ghislaine Maxwell flew to New York on 5 November 1990 to deliver an envelope on her father's behalf that, unknown to her, was part of "a plot initiated by her father to steal $200m" from Berlitz shareholders.[25]

After Robert Maxwell purchased the New York Daily News in January 1991, he sent Ghislaine to New York City to act as his emissary.[19][29] In May 1991, Maxwell and her father took Concorde on business to New York, from where he soon departed for Moscow and left her to represent his interests at an event honouring Simon Wiesenthal.[30]

In November 1991, Robert Maxwell's body was found floating in the sea near the Canary Islands and the Lady Ghislaine.[31] Soon afterwards, Ghislaine flew to Tenerife, where the yacht was berthed, to attend to his business paperwork.[19] Ghislaine attended her father's funeral in Jerusalem alongside Israeli intelligence figures, president Chaim Herzog, and prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, who gave his eulogy.[32][33] Although a verdict of death by accidental drowning was recorded, Maxwell has since said she believes her father was murdered,[34] commenting in 1997: "He did not commit suicide. That was just not consistent with his character. I think he was murdered."[35] After his death, Robert Maxwell was found to have fraudulently appropriated the pension assets of Mirror Group Newspapers, a company that he ran and in which he held a large share of ownership, to support its share price.[36] Pension funds in excess of £400m were said to be missing, and 32,000 people were affected.[37] Two of Maxwell's brothers, Ian and Kevin, who were the most involved with their father in daily business dealings, were arrested on 19 June 1992 and charged with fraud related to the Mirror Group pension scandal.[38] The brothers were acquitted three and a half years later in January 1996.[39]

Ghislaine Maxwell moved to the United States in 1991, shortly after her father's death. She was photographed boarding a Concorde to cross the Atlantic.[16][17] Maxwell was provided with an annual income of £80,000 from a trust fund established in Liechtenstein by her father.[40][41] By 1992, she had moved to an apartment of an Iranian friend overlooking Central Park. At the time, Maxwell worked at a real estate office on Madison Avenue and was reported to be socialising with celebrities.[42] She quickly rose to wider prominence as a New York City socialite.[17][43]

Ghislaine Maxwell's Relationship with Jeffrey Epstein

Accounts differ on when Maxwell first met American financier Jeffrey Epstein. According to Epstein's former business partner, Steven Hoffenberg, Robert Maxwell introduced his daughter to Epstein in the late 1980s.[44] The Times reported that Maxwell met Epstein in the early 1990s at a New York party following "a difficult break-up with Count Gianfranco Cicogna Mozzoni" (1962–2012) of the CIGA Hotels clan.[45]

Maxwell had a romantic relationship with Epstein for several years in the early 1990s and remained closely associated with him for more than 25 years until his death in 2019.[17][43][46] The nature of their relationship remains unclear. In a 2009 deposition, several of Epstein's household employees testified that Epstein referred to her as his "main girlfriend" who also hired, fired, and supervised his staff, starting around 1992.[47] She has also been referred to as the "Lady of the House" by Epstein's staff and as his "aggressive assistant".[48] In a 2003 Vanity Fair profile on Epstein, author Vicky Ward said Epstein referred to Maxwell as "my best friend".[49] Ward also observed that Maxwell seemed "to organize much of his life".[49]

Politico reported that Maxwell and Epstein had friendships with several prominent individuals in elite circles of politics, academia, business and law, including former Presidents Donald Trump and Bill Clinton, attorney Alan Dershowitz, and Prince Andrew, Duke of York.[50]

Maxwell is known for her longstanding friendship[51] with Prince Andrew, and for having escorted him to a "hookers and pimps" social function in New York.[52] She introduced Epstein to Prince Andrew, and the three often socialised together.[53] In 2000, Maxwell and Epstein attended a party thrown by Prince Andrew at the Queen's Sandringham House estate in Norfolk, England, reportedly for Maxwell's 39th birthday.[54] In a November 2019 interview with the BBC, Prince Andrew confirmed that Maxwell and Epstein had attended an event at his invitation, but he denied that it was anything more than a "straightforward shooting weekend".[55]

In 1995, Epstein renamed one of his companies the Ghislaine Corporation; based in Palm Beach, Florida, the company was dissolved in 1998.[47] As a trained helicopter pilot, Maxwell also transported Epstein to his private Caribbean island.[56][6]

In 2008, Epstein was convicted of soliciting a minor for prostitution and served 13 months of an 18-month jail sentence. Following Epstein's release, although Maxwell continued to attend prominent social functions, she and Epstein were no longer seen together publicly.[9]

By late 2015, Maxwell had largely retreated from attending social functions.[9][57]

Civil cases and accusations involving Ghislaine Maxwell

Virginia Giuffre v. Maxwell (2015)

Details of a civil lawsuit, made public in January 2015, contained a deposition from "Jane Doe 3" that accused Maxwell of recruiting her in 1999, when she was a minor, and grooming her to provide sexual services for Epstein.[17] A 2018 exposé by Julie K. Brown in the Miami Herald revealed Jane Doe 3 to be Virginia Giuffre, who was previously known as Virginia Roberts. Giuffre met Maxwell at Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida, when Giuffre was a 16-year-old spa attendant.[17] She asserted that Maxwell had introduced her to Epstein, after which she was "groomed by the two [of them] for his pleasure, including lessons in Epstein's preferences during oral sex".[17][58]

Maxwell has repeatedly denied any involvement in Epstein's crimes.[46] In a 2015 statement, Maxwell rejected allegations that she has acted as a procurer for Epstein and denied that she had "facilitated Prince Andrew's [alleged] acts of sexual abuse". Her spokesperson said "the allegations made against Ghislaine Maxwell are untrue" and she "strongly denies allegations of an unsavoury nature, which have appeared in the British press and elsewhere, and reserves her right to seek redress at the repetition of such old defamatory claims".[53][59]

Giuffre asserted that Maxwell and Epstein had trafficked her and other underage girls, often at sex parties hosted by Epstein at his homes in New York, New Mexico, Palm Beach, and the United States Virgin Islands. Maxwell called her a liar. Giuffre sued Maxwell for defamation in federal court in the Southern District of New York in 2015. While details of the settlement have not been made public, in May 2017 the case was settled in Giuffre's favour,[60] with Maxwell paying Giuffre "millions".[61]

Sarah Ransome v. Epstein and Maxwell (2017)

In 2017, Sarah Ransome filed a suit, in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, against Epstein and Maxwell, alleging that Maxwell hired her to give massages to Epstein and later threatened to physically harm her or destroy her career prospects if she did not comply with their sexual demands at his mansion in New York and on his private Caribbean island, Little Saint James. The suit was settled in 2018 under undisclosed terms.[9][43][62][63]

Affidavit filed by Maria Farmer (2019)

On 16 April 2019, Maria Farmer went public and filed a sworn affidavit in federal court in New York, alleging that she and her 15-year-old sister, Annie, had been sexually assaulted by Epstein and Maxwell in separate locations in 1996. Farmer's affidavit was filed in support of a defamation suit by Virginia Giuffre against Alan Dershowitz.[64] According to the affidavit, Farmer had met Maxwell and Epstein at a New York art gallery reception in 1995. The affidavit says that in the summer of the following year, they hired her to work on an art project in billionaire businessman Leslie Wexner's Ohio mansion, where she was then sexually assaulted by both Maxwell and Epstein.[65][66] Farmer reported the incident to the New York Police Department and the FBI.[47][67] Her affidavit also stated that during the same summer, Epstein flew her then 15-year-old sister, Annie, to his New Mexico property where he and Maxwell molested her on a massage table.[68][69]

Farmer was interviewed for CBS This Morning in November 2019 where she detailed the 1996 assault and alleged that Maxwell had repeatedly threatened both her career and her life after the assault.[70]

Jennifer Araoz v. Epstein's estate, Maxwell, and Jane Does 1–3 (2019)

On 14 August 2019, Jennifer Araoz filed a lawsuit in New York County Supreme Court against Epstein's estate, Maxwell, and three unnamed members of his staff; the lawsuit was made possible under New York state's new Child Victims Act, which took effect on the same date.[71] Araoz later amended her complaint on 8 October 2019 with the names of the previously unidentified women enablers to include Lesley Groff, Cimberly Espinosa, and the late Rosalyn Fontanilla.[72]

Priscilla Doe v. Epstein's estate (2019)

Ghislaine Maxwell was named in one of three lawsuits filed in New York on 20 August 2019 against the estate of Jeffrey Epstein.[73] The woman filing the suit, identified as "Priscilla Doe", claimed that she was recruited in 2006 and trained by Maxwell with step-by-step instructions on how to provide sexual services for Epstein.[74][75]

Annie Farmer v. Maxwell and Epstein's Estate (2019)

Annie Farmer, represented by David Boies, sued Maxwell and Epstein's estate in Federal District Court in Manhattan in November 2019, accusing them of rape, battery and false imprisonment and seeking unspecified damages.[76][77]

Jane Doe v. Maxwell and Epstein's Estate (2020)

In January 2020, a lawsuit was filed against Maxwell and Epstein alleging that they recruited a 13-year-old music student at the Interlochen Center for the Arts in the summer of 1994 and subjected her to sexual abuse.[76][78] The suit states that Jane Doe was repeatedly sexually assaulted by Epstein over a four-year period and that Maxwell played a key role both in her recruitment and by participating in the assaults.[76] According to the lawsuit, Jane Doe was targeted by Epstein and Maxwell for being fatherless and from a struggling family, in much the same manner as many of the other alleged victims.[78]

Maxwell v. Epstein's Estate, Darren K. Indyke, Richard D. Kahn, and NES LLC (2020)

On 12 March 2020, Maxwell filed a lawsuit in Superior Court in the US Virgin Islands seeking compensation from Epstein's estate for her legal costs.[79][80] Maxwell claimed she had been a longtime employee of Epstein (from 1998 to 2006)[81] who had served to manage his property holdings in the US Virgin Islands, New York, New Mexico, Florida and Paris[82] while continuing to deny any knowledge or involvement in his criminal activities.[79][80] According to the lawsuit, Maxwell was seeking damages for the legal fees associated with defending herself against her accusers, expenses that she claims Epstein had promised to cover for her.[79][80]

Jane Doe v. Epstein's estate (2021)

Maxwell was named in a civil suit filed against Epstein's estate in March 2021 by a Broward County woman who accused Epstein and Maxwell of trafficking her after repeatedly raping her in Florida in 2008.[83]

Dispute over release of Maxwell court documents

On 2 July 2019, the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ordered the unsealing of documents from the earlier civil suit against Maxwell by Virginia Giuffre.[84] Jeffrey Epstein was arrested on 6 July 2019 at Teterboro Airport in New Jersey and charged with sex trafficking and sex trafficking conspiracy.[85]

Maxwell requested a rehearing in a federal appeals court on 17 July 2019, in an effort to keep documents sealed that were part of a suit by Giuffre.[86] On 9 August 2019, the first batch of documents was unsealed and released from the earlier defamation suit by Giuffre against Maxwell.[87] Epstein was found dead on 10 August 2019, after reportedly hanging himself in his Manhattan prison cell.[88][89]

Maxwell and her lawyers continued to argue against the further release of court documents in December 2019.[90] Reuters confirmed on 27 December 2019 that Maxwell was under investigation by the FBI for facilitating Epstein's criminal activities.[91]

Additional documents from the Giuffre v. Maxwell defamation suit were released on 30 July 2020.[92] The documents included a deposition given by Giuffre and more recent email exchanges between Maxwell and Epstein,[92] with some of the correspondence from 2015.[44]

Court livestream controversy

On 19 January 2021, a court hearing was disrupted by believers in QAnon – who believe Maxwell to be working in cohort with a cabal of child-sacrificing Satanist liberal elites who traffic children for sex – as the proceedings were illegally livestreamed to YouTube.[93][94]

Arrest and indictment

Attempts to locate Maxwell to serve court documents

On 27 December 2019, Reuters reported that Maxwell was among those under FBI investigation for facilitating Epstein.[91] After his arrest, Maxwell was in hiding, communicating with the courts only through her lawyers who, as of 30 January 2020, had refused to accept on her behalf service of three lawsuits against her.[76] The New York Times reported that by 2016, Maxwell was no longer being photographed at events.[9] By 2017, her lawyers claimed before a judge that they did not know her address; they further stated that she was in London but they did not believe she had a permanent residence.[9]

Maxwell has a history of being unreachable during legal proceedings.[76][95][96][97] During the lawsuit filed in 2017 from Ransome against Maxwell, District Judge John G. Koeltl granted a motion for "alternative service" on the grounds that the plaintiff's efforts to reach Maxwell were persistently thwarted; these included hiring a private investigation firm that attempted service at three physical addresses, sending information to several email addresses, and reaching out to the lawyers actively representing Maxwell in another lawsuit who refused to become a "general agent of process" to relay the information to her.[96]

According to court documents from a lawsuit filed by Epstein against Bradley Edwards (a representative for several of his accusers), in 2010 Maxwell had agreed to provide a deposition in the case but reportedly left the country one day before Edwards was scheduled to fly to New York to take her deposition, "claiming she needed to return to the United Kingdom to be with her deathly ill mother"[97] with no intention of returning to the United States.[95] However, Maxwell returned within a month to attend Chelsea Clinton's wedding.[95]

In January 2020, it was reported that Maxwell had refused to allow her lawyers to be served with several lawsuits in which she has been directly named in 2019 and 2020, including one by Farmer and from Araoz.[76] While Maxwell's lawyers continued to argue on her behalf against the release of additional court documents from the Giuffre v. Maxwell lawsuit,[90] they claimed to not know where she was or to have permission to accept the lawsuits filed against her.[76][66]

Authorities in the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) were unsuccessful in locating Maxwell during the three and a half months they were seeking to serve her with a subpoena.[98] USVI prosecutors consider Maxwell to be a "critical fact witness" in their lawsuit against Epstein's estate.[98] A court filing from the USVI Department of Justice, released on 10 July 2020, stated that Maxwell was also under investigation for her alleged participation in Epstein's sex trafficking operation in the US Virgin Islands.[99]

Ghislaine Maxwell's Arrest in July 2020

Maxwell faced persistent allegations of procuring and sexually trafficking underage girls for Epstein and others, charges she has denied.[9] Maxwell was arrested in Bradford, New Hampshire by the FBI on 2 July 2020, through the use of an IMSI-catcher ("stingray") mobile phone tracking device on a phone used by her to call one of her lawyers, her husband Scott Borgerson, and her sister Isabel.[100]

Legal proceedings

Maxwell was charged with enticement of minors, sex trafficking of children, and perjury.[10][101][102] On 14 July 2020, federal Judge Alison Nathan of the Southern District of New York denied Maxwell bail after determining that her risks of fleeing "are simply too great".[103] Prosecutors, led by United States District Attorney Audrey Strauss, charged her with six federal crimes, including enticement of minors, sex trafficking, and perjury.[101][104][105][106] The indictment charged that between 1994 and 1997, she "assisted, facilitated, and contributed" to the abuse of minor girls despite knowing that one of three unnamed victims was 14 years old.[107]

As of 28 April 2021, Maxwell was being held at the Metropolitan Detention Center, Brooklyn, New York.[108][109][110] Lawyers requested that Judge Nathan release her on $5 million bond with monitored home confinement while awaiting trial.[111] Maxwell's attorney reiterated her request for bail on 18 December 2020, her attorneys indicating that Maxwell could reside with a friend in New York City during which time she would be under 24-hour surveillance as she awaited her July trial if she was released on bail.[112] She would not be staying with Borgerson, who has made a secured offer of US$22 million to guarantee her presence at future appearances. The bail request was considered by Judge Nathan, who rejected a US$5 million bail package for Maxwell in July 2020. At that time, Nathan had agreed with prosecutors that Maxwell was an "extreme flight risk."[112] Maxwell had appeared by video link before a court in Manhattan on 14 July 2020. She pleaded not guilty to the charges.[113] A naturalised US citizen since 2002 who also holds passports from France and the United Kingdom, Maxwell was denied bail as a flight risk amid concerns regarding her "completely opaque" finances, her skill at living in hiding, and the fact that France does not extradite its citizens.[103][111][114][115][116] Her lawyers argued unsuccessfully that she was at risk of catching COVID-19 in detention. The judge set a trial date of 12 July 2021.[113][117][118]

On 28 December 2020, a further request for bail was again rejected by a judge.[119] Maxwell's bail request was opposed by alleged victim Annie Farmer.[112]

On 26 January 2021, a motion by Maxwell's attorneys challenged her grand jury indictment, claiming that it did not reflect the ethnic diversity of the jurisdiction in which the violations of the law were alleged to have occurred.[120]

On 29 March 2021, US prosecutors added new charges of sex trafficking a minor and sex trafficking conspiracy, alleging that Maxwell was involved in grooming a fourth girl, aged 14, to engage in sexual acts with Epstein between 2001 and 2004 at his Palm Beach estate.[121][122] Maxwell appeared in court on 23 April 2021 and pleaded not guilty to the additional charges; she faces six counts that include sex trafficking of a minor and sex trafficking conspiracy, in addition to two counts of perjury.[123]

Maxwell's attorneys have regularly protested about the conditions of her confinement. These include being kept awake by a light shined in her eyes every fifteen minutes to deter the chances of her committing suicide, and being denied a sleep mask.[124] One, David Marcus, protested, "There's no evidence she's suicidal. They're doing it because Jeffrey Epstein died on their watch", and that, "She's not Jeffrey Epstein, this isn't right".[124]

Sex-trafficking trial

In April 2021, US District Judge Alison Nathan ruled that Maxwell would face two separate trials, one for the sex trafficking charges and another for perjury.[125] In May 2021, Nathan delayed the trial to 29 November 2021 after Maxwell's defence lawyers successfully argued that the sex trafficking charges added in March 2021 gave them insufficient time to investigate the new charges and prepare for trial.[126] Maxwell appeared in court on 15 November 2021.[127] The trial commenced on 29 November 2021 with opening statements.[126] Twelve jurors had been picked, plus six alternates, from a pool of forty to sixty people.[128]

It was announced in November 2021 that psychologist Elizabeth Loftus, an expert on false memory syndrome, would be called as an expert witness for the defense.[129]

On 28 December, as the jury completed its fourth full day of deliberations, judge Nathan said she feared jurors and trial participants might become infected with COVID-19 and forced to quarantine, raising the possibility of a mistrial. She later said that she had extended the jury's hours to 6 p.m. and would also have deliberations continue through the holiday weekend until the jury reached a verdict.[130][131]

Conviction of Ghislaine Maxwell

On 29 December 2021, Maxwell was convicted by a jury in US federal court on five sex trafficking-related counts carrying a potential custodial sentence of up to 65 years imprisonment: one of sex trafficking of a minor (maximum: 40 years), one of transporting a minor with the intent to engage in criminal sexual activity (10 years) and three of conspiracy to commit also-charged choate felonies (15 years total).

She was acquitted on the charge of enticing a minor to travel to engage in illegal sex acts.[2][3][4] Her family said they had commenced the appeal process.[132][133]

Perjury trial of Ghislaine Maxwell

Maxwell will face trial, probably in 2022, on two charges that she lied under oath about Epstein's abuse of underage girls, which each carry a maximum sentence of five years in prison.[134][135]

TerraMar Project

In 2012, Maxwell founded The TerraMar Project,[136] a nonprofit organisation that advocated the protection of oceans. She gave a lecture for TerraMar at the University of Texas at Dallas and a TED talk, at TEDx Charlottesville in 2014.[137] Maxwell accompanied Stuart Beck, a 2013 TerraMar board member, to two United Nations meetings to discuss the project.[28]

The TerraMar Project announced closure on 12 July 2019, less than a week after the charges of sex trafficking brought by New York federal prosecutors against Epstein became public.[9] An associated, UK-based company, Terramar (UK), listed Maxwell as a director.[138] An application for the United Kingdom organisation to be closed was made on 4 September 2019, with the first notice in The London Gazette made on 17 September 2019.[139] The company Terramar (UK) was listed as officially dissolved on 3 December 2019.[139]

Personal life of Ghislaine Maxwell

Since at least 1997, Maxwell has maintained a residence in Belgravia, London.[140][141] In 2000, Maxwell moved into a 7,000 sq ft (650 m2) townhouse on East 65th Street, New York City, fewer than 10 blocks from Epstein's mansion. Maxwell's townhouse was purchased for US$4.95 million by an anonymous limited liability company, with an address that matches the office of J. Epstein & Co. Representing the buyer was Darren Indyke, Epstein's longtime lawyer.[9] In April 2016, the New York townhouse where she had lived was sold for US$15 million.[9]

Following her personal and professional involvement with Epstein, Maxwell was romantically linked for several years to Ted Waitt, founder of Gateway Computers.[28][142] She attended the wedding of Chelsea Clinton in 2010 as Waitt's guest.[28] Maxwell helped Waitt obtain and renovate a luxury yacht, the Plan B, and used it for travel to France and Croatia before their relationship ended, in late 2010[26] or early 2011.[17][28]

On 15 August 2019, reports surfaced that Maxwell had been living in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, in the home of Scott Borgerson, who in October 2020, due to the publicity surrounding Maxwell, stepped down as CEO of CargoMetrics,[143] a hedge fund investment company involved in maritime data analytics.[26][144][145] Maxwell and Borgerson were described as having been in a romantic relationship for several years.[26][144][146] Locals in the town of Manchester-by-the-Sea said Maxwell had kept a low profile, went by "G" instead of her full first name, and had been seen on several occasions walking a Vizsla dog along the beach.[147][148]

Borgerson and Maxwell filed documents in Massachusetts Land Court about Borgerson's residence, known as Phippin House, during a civil dispute with neighbours regarding rescinded access rights to the larger Sharksmouth Estate in 2019.[149] A neighbouring property manager attested that Maxwell and Borgerson were living together at the property in question.[150] Others have said they had been seen repeatedly running together in the mornings.[145]

Borgerson stated in August 2019 that Maxwell was not currently living at the home and that he did not know where she was.[144] On 15 August 2019, the New York Post published photographs of Maxwell dining at a fast-food restaurant in Los Angeles, claiming that "The Post found the socialite hiding in plain sight in the least likely place imaginable — a fast-food joint in Los Angeles".[151] The photos were later proven to have been taken at a meeting with Maxwell's friend and attorney Leah Saffian, who also gave other pictures to the Daily Mail.[152][153]

Maxwell moved to a remote 156-acre (63 ha) property in Bradford, New Hampshire in late 2019,[154] where she used former British military personnel as personal security until her arrest in July 2020.[109] At the time of her arraignment, federal prosecutors stated that Maxwell was married; she did not disclose the identity of her spouse (or their respective finances).[155]

In December 2020, it emerged that she had married Borgerson in 2016.[156][157][112]

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b Davis O’Brien, Rebecca; Paul, Deanna (2 July 2020). "Jeffrey Epstein Associate Ghislaine Maxwell Arrested on Federal Charges". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hays, Tom; Neumeister, Larry (29 December 2021). "Ghislaine Maxwell convicted in Epstein sex abuse case". Associated Press. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cohen, Luc (29 December 2021). "Ghislaine Maxwell convicted of setting up girls for Epstein sex abuse". Reuters. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c del Valle, Lauren (29 December 2021). "Jury finds Ghislaine Maxwell sex trafficked a minor for Jeffrey Epstein, guilty on five of six counts". CNN US. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Haines, Joe (1988). Maxwell. London: Futura. pp. 434 et seq. ISBN 0-7088-4303-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Sampson, Annabel (15 August 2019). "Who is Ghislaine Maxwell, the British socialite at the centre of the Jeffrey Epstein scandal". Tatler. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan; Freifeld, Karen (23 April 2021). "Ghislaine Maxwell pleads not guilty to sex trafficking". Reuters. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Ghislaine Maxwell convicted in Jeffrey Epstein sex abuse case: Live updates". AP NEWS. 29 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l Twohey, Megan; Bernstein, Jacob (15 July 2019). "The 'Lady of the House' Who Was Long Entangled With Jeffrey Epstein". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ghislaine Maxwell, Accused of Providing Girls for Jeffrey Epstein, Arrested in N.H." New Hampshire Public Radio. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Betty Maxwell Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Maxwell, Elisabeth (1994). A Mind of My Own: My Life with Robert Maxwell. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. p. [1]. ISBN 0060171049.

- ^ Stevenson, Tom (29 May 1993). "Maxwell home sold – with tenant: Tycoon's widow may stay at Headington another six years". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ McFerran, Ann (11 April 2004). "Relative Values: Elisabeth Maxwell, the widow of Robert Maxwell, and their daughter Isabel". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ffrench, Andrew (3 August 2021). "Before meeting Jeffrey Epstein, Ghislaine Maxwell was an Oxford United director". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Davies, Caroline (4 January 2015). "Court papers put daughter of Robert Maxwell at centre of 'sex slave' claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Schneier, Matthew (15 July 2019). "Ghislaine Maxwell, The Socialite on Jeffrey Epstein's Arm". New York. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Willis, Tim (April 2000). "Tatler Archive: The return of the Maxwells, as Ghislaine is finally found". Tatler. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Bower, Tom (12 August 2019). "Ghislaine Maxwell, daughter of Robert Maxwell, fell under the spell of rich and domineering men". The Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ Cranley, Ellen (8 July 2019). "What to know about British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein's alleged madam". Insider. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ Field, Ophelia (2009). Kitten Club: Friends who Imagined a Nation. Harper Press. p. 379.

- ^ "Profile of Ghislaine Maxwell" Archived 26 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Walker's Research

- ^ David Crabtree, et al "A History of Oxford United Football Club" Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, OUFC website, 8 March 2011

- ^ Whitworth, Damian (13 August 2019). "The socialite and the Epstein scandal: Ghislaine Maxwell's life and times". The Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bower, Tom (11 January 2015). "Out from Cap'n Bob's shadow and into a web of sex and royals". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Bernstein, Jacob (14 August 2019). "Whatever Happened to Ghislaine Maxwell's Plan to Save the Oceans?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Misery in the Maxwell House". The Scotsman. 16 November 2001. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Schreckinger, Ben; Lippman, Daniel (21 July 2019). "Meet the woman who ties Jeffrey Epstein to Trump and the Clintons". Politico. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Fry, Naomi (16 August 2019). "The Gall of Ghislaine Maxwell". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Bower, Tom (12 August 2019). "Ghislaine Maxwell, daughter of Robert Maxwell, fell under the spell of rich and domineering men". The Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ "Family Misfortunes", 21 January 1996, The Observer, page 14

- ^ Biedermann, Florence (4 July 2020). "The Maxwells: Scandal, conspiracy and more than a few days in court". Time of Israel. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Diehl, Jackson; Frankel, Glenn (11 November 1991). "Israel Gives Maxwell Farewell Fit For Hero". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (20 February 1997). "Shot in the dark?". The Guardian. London, England.

- ^ "Soundbites", The Observer, 23 February 1997

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (6 March 2011). "Ghislaine Maxwell: Press baron's daughter and Epstein's former lover". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "The Pensioners' Tale". BBC News. 29 March 2001. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewan (19 June 1992). "Maxwell's Sons Arrested on Fraud, Theft Charges". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "The way is still clear for a tyrant and a fraud". The Independent. 20 January 1996. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Brown, David; Keate, Georgie; Spence, Matt (6 January 2015). "'Madam' Maxwell linked to film stars and top politicians". The Times. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Mick Brown and Harriet (3 January 2020). "The rise and fall of socialite Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein's 'best friend'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Davison, John (7 June 1992). "All right for some; Maxwell family". The Sunday Times. p. 11.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Arnold, Amanda (12 July 2019). "Everything We Know About Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein's Alleged Madam". New York. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Helderman, Rosalind S.; Fisher, Marc (31 July 2020). "Before President Trump wished Ghislaine Maxwell 'well,' they had mingled for years in the same gilded circles". Washington Post. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Jeffrey Epstein obituary". The Times. 10 August 2019. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Ghislaine Maxwell: profile". The Daily Telegraph. 7 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hong, Nicole; Davis O'Brien, Rebecca (11 July 2019). "Following Epstein's Arrest, Spotlight Shifts to Financier's Longtime Associate". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Abrams, Margaret (19 July 2019). "Who is Ghislaine Maxwell? The life of Jeffrey Epstein's former socialite girlfriend and alleged 'madam'". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ward, Vicky (27 June 2011). "The Talented Mr. Epstein". Vanity Fair (published March 2003). Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Forgey, Quint (4 August 2020). "Trump doubles down on well-wishes for alleged sex trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell". Politico. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Ross, Martha (3 December 2019). "Prince Andrew and Ghislaine Maxwell are still chums and still talk, reports say". The Mercury News. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Wells, Matt (10 April 2001). "New role for Andrew in doubt after royal fiasco". The Guardian. London, England.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rayner, Gordon (2 January 2015). "Prince Andrew 'categorically denies' claims he sexually abused teenager". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Patterson, James (2016). Filthy Rich. New York: Little Brown and Company. pp. 216, 221. ISBN 978-0-316-27405-0.

- ^ "Prince Andrew Newsnight interview: Transcript in full". BBC News. 17 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Hurtado, Patricia; Alexander, Sophie (17 July 2020). "Mystery of Ghislaine Maxwell's Wealth Hangs Over Case". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 July 2020 – via Time.

- ^ Shubber, Kadhim (16 August 2019). "Epstein scandal's pressing issue: the role of Ghislaine Maxwell". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Brown, Julie K. (28 November 2018). "Even from jail, sex abuser manipulated the system. His victims were kept in the dark". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Statement on Behalf of Ghislaine Maxwell" (Press release). Devonshires Solicitors. PR Newswire. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Russell, John (25 May 2017). "Billionaire's Alleged Sex Slave Settles Libel Case". Courthouse News Service. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Brown, Julie K. (1 March 2019). "Alan Dershowitz suggests curbing press access to hearing on Jeffrey Epstein sex abuse". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Brown, Julie K. (7 July 2019). "With Jeffrey Epstein locked up, these are nervous times for his friends, enablers". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Dickson, EJ (9 July 2019). "Who Is British Socialite Ghislaine Maxwell, Jeffrey Epstein's Longtime Partner?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Ellison, Sarah; O'Connell, Jonathan (5 October 2019). "Epstein accuser holds Victoria's Secret billionaire responsible, as he keeps his distance". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Brown, Julie K. (16 April 2019). "New Jeffrey Epstein Accuser Goes Public: Defamation Lawsuit Targets Dershowitz". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Saner, Emine (12 December 2019). "'She was so dangerous': where in the world is the notorious Ghislaine Maxwell?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Hill, James; Remillard, Mark; Effron, Lauren (9 January 2020). "Jeffrey Epstein survivor paints portraits of other survivors: 'Each one of those should have never happened'". ABC News. Retrieved 11 February 2020.